Part two of our trip to Uzbekistan

The unpleasantness didn’t end when our eight hour journey to Bukhara did. Our driver, Goldtooth Punchdrunk, was pissed when he discovered we had already arranged accommodation in Bukhara, meaning he would miss out on a hotel’s commission. He threatened to drop us at the outskirts of town then he said we underpaid him (we hadn’t). The manager at our Bukhara hotel said Goldtooth was a little stupid, I tend to agree with him. Unpleasantness over, our lodgings in Bukhara were much grander than we were used to. For a start, there was a TV in the room and the shower had pressure. Our room had been decorated to resemble a famous palace in Samarkand, with fabulous painted murals (they had even recreated the damage done on the original murals). The dining room was the unrenovated room of a 19th Century Jewish merchant. A large Jewish population had lived here once, co-existing with Muslims, even using a mosque as a place of worship before the first synagogue was built in 1620. Now, no more than a thousand Jews live in the city, most having left for Israel or America during Soviet times.

|

| The dining room of our hotel. |

|

| Lyabi Hauz, a tranquil spot. Beware of the shashlik though. |

The atmosphere around the pool was great, the food poor and I’m sure the shashlik kebabs were the cause of discomfort I had later in the trip. There was a horde of begging cats that came crawling onto our divan, trying to score some meaty bits of mutton. Even some Muscovy ducks begged for scraps. A statue of Nasruddin Hoja, the wise Sufi fool (yes, that an oxymoron but that is how he is described) sits near the pool, a popular photo opportunity for tourists and something for the local kids to clamour over. Just past Lyabi-Hauz were the first of several domed covered bazaars, filled with souvenir stalls selling carpets, traditional embroidery, hats and trinkets, a reminder that once Bukhara was a thriving and important city, one of the key stops on the old Silk Road. It was also one of the most prominent Islamic cities, known as the Pillar of Islam; Bukhoro-i-Sharif (noble Bukhara) was the name given to signify its holiness, serving as the heart of Islam in Central Asia. Not surprisingly, the oldest mosque in Central Asia is here, the 9th Century Pit of the Herbalists (Maghoki-Attar), standing on top of an old Buddhist and Zoroastrian sight, now acting mainly as a museum and shop.

|

| Pulling at the medressa. |

Bukhara is also famed for its wonderfully restored medressas, again the oldest in this part of the world. The oldest one dates to 1417 (the Mongols destroyed earlier medressas during the conquests of Genghis Khan). Medressas are Islamic schools attended by the rich and smart children. The students (all boys) lived together in small rooms and received tuition from their teachers; 2 students to a teacher, a student: teacher ratio today's parents would approve of. Study began at the age of 12 and lasted for up to ten years; memorizing the Koran and taking subjects such as mathematics, theology, philosophy and astronomy. Medressas were banned upon the arrival of the Red Army and subsequent integration into the Soviet Union. Many of the medressas were destroyed, used as warehouses or turned into musuems. Some in Bukhara have reverted back to their original function but most stand idle, used as glorified souvenir stands and ogled by tourists.

Bukhara’s biggest claim to fame is not its shopping or its Islamic schools anymore (as a sidenote, the shopping was probably the best in the country). It’s most famed for its architecture, in particular the Ark and the area around the Kalon Minaret. Fitzroy Maclean, a British adventurer through Central Asia in the 1930s, described it as ”an enchanted city” with buildings that rivalled “the finest architecture of the Italian Renaissance”. It, like Khiva, has been granted UNESCO World Heritage status, who said that it “represents the most complete example of a medieval city in Central Asia, with a fabric that remained largely intact”. Here, the tile-work was ornate and colourful, which contrasted to Khiva’s mostly mud-brick unadorned structures, with large turquoise-coloured domes, huge mosaic door arches and tall minarets.

|

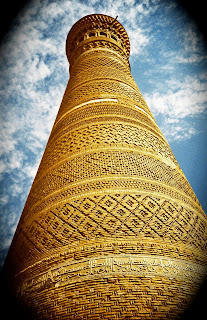

| Kalon Minaret, beautiful detail. |

Bukhara’s most famed structure is the Kalon Minaret, 45 metres tall, meaning it was probably the tallest structure in Cental Asia at the time it was built. It was apparently such an awe-inspiring sight that even Genghis Khan chose to spare it during his destructive rampage through Central Asia in the 13th Century, despite burning almost every other building in the city and indeed the whole of Central Asia. At first glance, it looks relatively plain but when you look more closely at it, you can see its inherent beauty. On a day like the day we saw it, its colour contrasts magnificently against the rich blue sky. The lower section has intricately carved calligraphy that is said to include the name of the architect, the date of construction, the name of the benefactor who paid for its construction as well as quotes from the Koran. Up higher, it has fourteen sections of mud-brick tiles, varying in design, marking vertical delineations up the entire length of the minaret. One of the top sections has the first recorded use of the glazed blue tiles that were so prominent in latter Uzbekistan architecture.

|

| Kalon Minaret and the Azerbaijan delegation. |

The minaret serves as the centrepiece of a small square that is flanked by a mosque and a medressa. Locals set up stalls here, selling ceramics, bread brushes and souvenirs. A young mother kicked a ball around with her two toddlers. The mosque, known as Kalon Mosque, was built on the site of one originally destroyed by the Mongols (obviously, the mosque was not as impressive as the minaret). It was used as a warehouse during Soviet times but now sees service as an active mosque, still being restored as we were there. A delegation from Azerbaijan pulled up as we arrived, so we didn’t go into the mosque itself, security being tight. We just admired it from the outside, its large, ornate gate flanked by two turquoise domes. Opposite is the 16th Century Mir-i-Arab medressa, which is now once again operating as a medressa. It was quiet here and we sat for a while. The courtyard had many niches and archways running off from it; a solitary tree sat in the middle of it. Sitting out the far end, you could see both the front gates of the mosque, medressa and minaret. It was quiet, beautiful and relaxing, one of the highlights of the trip.

|

| The courtyard of Mir-I-Arab medressa, looking towards Kalon Mosque and Medressa. |

My low point was not far away. The skashlik we had ate around Lyabi-Hauz was having its revenge, my stomach was in knots. I ran across the courtyard, stomach cramped, knees clenched. When I asked where the toilet was, flustered, red and sweaty, I was directed the way I had come, meaning a second, undignified dash of the courtyard, this time trailing behind a boy, who no doubt sensing my discomfort, ran to show me the location of the toilet. A group of angry, elderly French yelled out to me to get out of their shot, tourists made impatient by the lack of people in Uzbekistan, unable to wait to get a picture without people obscuring the view. I gave them little notice and ran on, only hoping that I would reach the toilet and not deface the courtyard. That I managed to reach the toilet came as a relief, both mentally and physically.

|

| Kalon Mosque. |

Bukhara had been one of the capitals of the khanates involved in the Great Game, the race between Tsarist Russia and the British Empire to win influence in Central Asia, (the Russians used the term Tournament of Shadows to describe it which I quite like). For the British, it meant safeguarding their biggest prize, India; for the Russians, it meant an opportunity to extend their influence throughout Asia, grow their empire and maybe eventually gain India for themselves. Bukhara played its part in this battle, which was mostly fought using espionage, spying and networking (although several wars, particularly those of the British in Afghanistan were brought about by fears over growing Russian influence in the region). One such war had happened in 1839. Britain sent an envoy, Colonel Stoddard, to Bukhara (then the capital of the Bukhara khanate, a significant state in Central Asia at the time) to reassure Bukhara’s emir over Britain’s intentions in Afghanistan. The emir, incensed by what he saw as deliberate snubs by the British, imprisoned Stoddard, throwing him into a vermin infested bug-pit behind the Ark where he languished for three years. For the last one of these three years, he was joined by a compatriot, Captain Conolly, who had arrived to try and secure Stoddard release in 1841. The emir mistrusted his motives, and believing him to be in cahoots with his rivals, the khanates of Khiva and Kokand, placed Conolly in the bugpit, along with Stoddard, rodents, snakes and bugs. In 1842, the two were marched out in to the Registan (town square) in front of a large crowd gathered to watch from the Ark, and amid loud cheering and playing of drums, were made to dig their own graves before being unceremoniously beheaded.

|

| The imposing walls of the Ark. |

The ark and square where this drama unfolded still stands. It is much larger than its equivalent in Khiva, with tall, mostly intact earthen walls 16 to 20 metres high that loom large over the surrounds. A camel sits under its shadow in the Registan, ready to pose for photos or take people for a ride. A donkey accompanies it so at least it has some company, unlike the lonely camels we had saw in Khiva and at Ayaz-Qala. It served as a city inside a city for the emirs and in times of strife. When the Mongols invaded, the town’s inhabitants sought refuge in the Ark and presumably found death there after the Mongols breeched the fortress walls. Much of the Ark was damaged during the Soviet invasion, both by bombing and possibly through the deliberate actions of the last emir, who ordered parts of the Ark (especially the harem) to de destroyed so as to prevent it being desecrated by the Soviets. It looks imposing, befitting the home of a major, local ruler. It was the survivor and last incarnation of several other buildings that have been raised and destroyed on this site, dating from at least 500 AD. As usual, the Ark had its own collection of souvenir shops and we met some young men selling artwork on the rooftop. One of them, who my travel companions described as the hottest guy in Uzbekistan (no doubt influencing their decision to buy pieces of art from him), had piercing blue eyes. The guy’s friend (Uzbekistan’s top model had little English) said that blue eyes were common in the village where the boy was from, a legacy of people from Macedonia (maybe even Alexander the Great’s soldiers). Alexander the Great had himself taken a Central Asian bride, Roxana, with whom he had a son. If hot guy’s eyes were a legacy of Alexander the Great’s march through here, it is quite remarkable that they could have persisted in the gene pool for so long and serve as an indicator of how Central Asia has been a crossroads between people for millennia.

|

| One of the domed bazaars. |

We had only two nights in Bukhara before we had to head off to Samarkand. We caught a taxi to take us to the train station. Of course, it was a Daewoo. Trains hold a certain appeal to me, although India has made me a little nervous of trains. I’ve been scarred by long waits on train platforms, fighting off flies, unsuccessfully trying to keep clean, being captivated yet disgusted by the antics of rats who proliferate at dawn or dusk, who find a livelihood amongst the train tracks, in Indian railway stations. I’m no Paul Theroux, who seems to thrive on train travel for the sake of it but it remains my preferred form of local transport. It allows freedom of movement (important for someone with a weak bladder who has almost been caught short several times on provincial buses in South-East Asia). The train ride from Bukhara to Samarkand proved to be so much easier than the taxi from Khiva had been (and much cheaper). Instead of being slowly stir-fried in the back of a taxi, we rolled our way across Uzbekistan. The train, known as the Sharq, (neither a reference to Shaquille O’Neal or the marine predator) was neither new nor old but it was comfortable, on time and quick and most thankfully, nothing like an Indian train. For a start, we had entertainment, a video (VHS is still king here) of a show done by a famous Uzbek performer. It was part Bollywood, part Turkish, heavily synthesized and choreographed with traditionally dressed backup dancers with a fondness for flowers. Outside, the desert was still there but civilization was fighting back. Fruit trees and cotton fields made this a greener journey. Samarkand beckoned, the last of the great Silk Road centres we were visiting. It had a lot of live up to. Bukhara had been wonderful. I'll finish with the words of Fitzroy Maclean again, “elsewhere in the world, light came down from heaven, but from Bukhara, it went up”.