It’s said cricket is a religion in India. It seems to be the one thing that all Indians can embrace. Separated by language, by caste, by religion, cricket serves as a common language, a thread tying communities together, be they Hindu, Muslim or Sikh. It also acted as a bridge for me, making a conversation easy to start, a disagreement easier to smooth over, a transaction easier to conduct. We encountered cricket everywhere. The first day in Dehli, we saw young men in white playing backyard cricket under the shadow of Humayuan’s Tomb. The day was hot, the setting epic and I stopped momentarily to watch these men play, amongst the dogs, pigeons and chipmunks, hopeful that they would maybe call me up for a hit. Later, we saw games played near the Jami Masjid, the largest mosque in the capital. In Agra, we met a Sikh jeweler who said he was a friend of David Boon’s, an Australian cricketer most famous for his drinking of over 60 cans of beer on a Sydney-London flight. I asked him if it was true “Yeah, mate” he replied in a thick Aussie accent, “Boonie’s a big drinker”. In Jaipur, I chatted cricket to our tuk-tuk drivers. Shane Warne, great Australian bowler and notorious womanizer, played for the team based in Jaipur. “Did Warne text your wife when he was here”, I asked, hoping that I hadn’t crossed the line. I hadn’t or at least he wasn’t perturbed enough by it to want to lose a fare.

Above: Cricket outside the Jama Masjid.

In Udaipur, I got my first chance of a game. Myself and one of my travelling companions played some street cricket with Danish, the son of the hotel owner where we were staying. Apparently, he had played age group cricket for Rajasthan, he may have been lying but he did look like a handy bowler. We played in a square with the famous lake forming one of the boundaries. Groups of smaller children sat interested on the sidelines, I’m sure hoping for a call up just like I had in Dehli. We played 6 a side, with a composite ball and Danish’s bat, a gift bought for him by some Danish tourists. The game was consistently stopped by lost balls, which went over fences, onto roofs, into shops or on unfortunate occasions the dump near the lake or even more unfortunately into the open sewers that ran down one side of the square. Here, the younger spectators proved their worth, pulling the ball out from the sewers and giving it a wipe with a towel so as to remove the gunk before passing it back to us for the game to continue. This may have been the root of my subsequent food poisoning.

The trek around India had been planned around arriving in Chandigarh so that we could watch the first day of the second test between India and Australia. Initially, it seemed my chances of procuring tickets weren’t good. People either said that I couldn’t buy them, that the game was sold out or that only Indians could buy them. In Amritsar, the city before Chandigarh, I asked the hotel manager if he could make enquires. He said that of course he could but it was no surprise to me when he told me the next day that there were no tickets. The man wouldn’t do anything without an ulterior motive, reminding me of a bearded lizard, his eyes hungry for new ways to nickel and dime tourists.

Discouraged by these answers, I resolved to wait until we arrived in Chandigarh to get tickets. Whether legit or black-market, it didn’t matter. I was prepared to pay an elevated price for the tickets, if need be. The day we arrived in Chandigarh, I took a tuk-tuk by myself down to the ground. The others wanted to rest up, we had been traveling pretty intensively and this was a rare afternoon off. I walked around for 20 minutes, being misdirected to the ticket office, which I finally stumbled on not inside the ground but outside. There was only a short queue for tickets, a good sign that there were still tickets available. After a short wait, it was my turn. Approaching the ticket box, I could see a big pile of tickets. I knew that the lizard king of Amritsar had been lying. My fear of not getting tickets was exposed to ridicule. Unlike in New Zealand, I could only buy tickets for the full five days, costing 1040 rupees, which come to 22 US dollars. The five of us were all on a tight budget and I remembered that the others didn’t share my enthusiasm for the great game so I enquired if they were any cheaper tickets. “Of course”, said the ticketmaster, “there are general admission, chair block for 300 rupees”. “Sounds perfect but is there no way to just buy tickets for the first day”, I enquired, out of hope more than anything. I got the expected answer but 300 rupees was still a reasonable price to pay.

Behind me, an older English woman enquired about the tickets, surprised as I had been by the fact that you couldn’t buy individual day tickets. It was her that planted the seed to what eventually led to my downfall. “I’m sure you could sell them off, the tickets for the days you don’t want”. Genius, I could make some money back for my friends. This was a mistake. It all started out OK though. I sold my first two tickets without a hitch, for a discounted price of 50 rupees, cheaper than what I paid for them. A boy in a wheelchair was next in line. This is when it all started to turn to custard. The crowd (for by this stage, the foreigner selling cheap tickets had drawn quite a crowd) started handing money over, snatching at tickets, I was pushed and jostled. Then come the hands. I had money in a money belt that I kept in my underpants. Hands there. I had put the tickets I want to keep down the back of my shorts. Hands there. Hands were on the tickets I was selling and hands were on the money I had got for selling the first few tickets. With what felt like 30 pairs of hands on me, I tried to break free from the melee. Cops still by idly across the road, barely 10 metres from this commotion. I yelled stupid made up insults like cow eater to try to offend the violators. The old English lady and her husband, perhaps feeling guilty that they has started this sequence of events, tried to come to my aid but the crowd wasn’t bowing to age. I made the decision to cut my losses and ran away from the crowd, to regroup and re-gather my thoughts, away from the melee. I had lost 3 of the first day tickets, which I would have to purchase again. All of the 20 tickets that I had been trying to sell had been taken, along with the money I had raised from selling the first few tickets. I did have just enough money to pay for the auto-rickshaw home and to re-buy the stolen tickets. I returned to the line, indignant at my treatment and bristling with anger. Those people that I recognized as some of my assaulters I glared at. Some of my fellow ticket buyers felt sorry and tried to comfort me. They said things like “this is not your country sir, this is India and India has no rules.” This didn’t really improve my mood, well intentioned or not. I waited in line to purchase my tickets, gave the unwanted tickets away to a polite teenage boy (my foray into the black-market was very short-lived) and got back to the hotel to relay my story to the others on what turned out to be quite an eventful night.

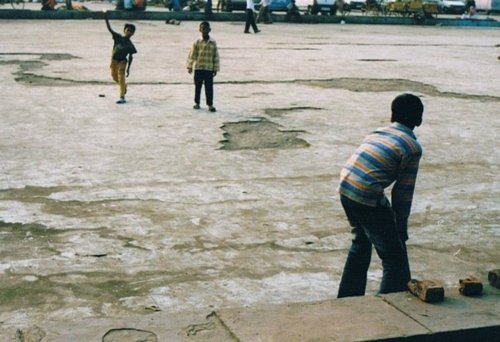

Above: Boys before the cricket.

Trying to forget my foray into the black market, I awoke the next day ready to actually see some cricket. The sun was out, promising a full day of play. Sensing that the others weren’t that keen to spend a whole day at the cricket, I promised that we could sit back, enjoy the sun and the cricket and have a few quiet beers. Fosters beer signs were everywhere around the ground and while not the best beer, there’s almost nothing better than watching cricket on a hot day with a cold beer. We made a couple of banners “I support two teams- New Zealand and anyone playing Australia” and “I’m Canadian eh, what the hell is cricket”, hoping that it would get us on T.V. At the ground, security was tight and our rickshaw could only get us within 500 metres of the ground. People were selling Indian flags, one of which I bought. Others offered face painting or had wristbands and bandanas for sale. The locals cheered at our Australian bashing banner, which was good as people before seeing it probably suspected us of being Australian. Australians jeered us. Contrary to what I was told the day before about India being a land of no rules, it turns out that India is actually a land of many rules. The first checkpoint saw us lose the Canadian banner, presumably because it said ‘hell’. Next, we were told no cameras. The pole from my Indian flag I had just purchased was confiscated. Finally, the girls weren’t allowed to take in their handbags. They retreated to find a hotel that would look after the bags while Chris and I continued on. After a couple more pat downs to make sure we didn’t have any concealed poles, obscene banners or cameras, we made it into ground. In the space of 24 hours, India had gone from no rules to the most bureaucratic, red tape loving nation on Earth.

Above: Mary with the Aussie bashing banner.

Inside the ground, I noticed four things. First of all, there were was hardly anyone in the ground. I had expected it to be near capacity. Instead, there were perhaps only 3000 people there. Most were school children bussed in from the surrounding area. They got in for free but had no money and were given no food or water. Second of all, we were the only foreigners in the cheap seats. All of the other foreigners had, maybe wisely, paid for tickets that were under shade. Thirdly, the Fosters beer was not beer at all, it was Fosters water. The ground was dry, it was like Prohibition from the 30s. Last of all, I noticed everyone had cameras. Everyone but us. The over-earnest security meant that we had missed the toss but the crowd informed us that India were to bat. Which was good because Sachin Tendulkar, the favourite son of Indian cricket, was only 30 runs away from becoming the highest run-scorer in test history. India made good progress and the crowd was in a good mood. They enjoyed the cricket but found the foreigners in the cheap seats more entertaining than the sport. They loved our sign and anti-Australian sentiments. They loved our poor attempts at speaking Hindi, Urdu and Punjabi. They delighted in our bhagra dancing in celebration of an Indian boundary (These poor attempts at dance not only impressed our fellow spectators but was sufficiently good enough to attract the attention of the TV crews). They especially loved the girls. Indian men have a way with women, but its not necessarily a good way. The banned for us cell phones were out in force taking pictures and videos of the foreigners, sometimes covertly and at other times, very obviously. Akon’s hit I wanna **** ya was played to the girls as a kind of electronic, none too subtle, serenade.

Unlike crowds in New Zealand, where opposition players get given a high level of vitriol, usually about their pedigree, their partner or their sexuality, the Australian players were confronted by bouts of non-ironic applause. The worst abuse I heard dished out all day was “Mitchell Johnson and Johnson Baby oil”, a far cry from the “Brett Lee’s a wanker” chants that reverberate around New Zealand stadia.

Above: On T.V

The abuse may not have been taxing but the Indian sun was, and my fellow travelers, newcomers to the sport of cricket, weren’t having as much fun as me. This is where the lack of Fosters really hurt me. Lunch break was a welcome interlude for them, the girls taking refuge from the Akon-playing shifty men in the cool, comparatively clean bathroom. Chris and I spent the time chatting with the locals, which further increased our notoriety. Being a foreigner is one thing, one who likes hanging out the locals is another. Our notoriety spread. Pleas for photos and company increased exponentially. We received requests to come and sit with such and such a group of supporters, doing half hour stints with the different factions. People would get jealous if we seemed to favour certain groups of people. Things could have turned ugly. Some relief came at the fall of the 2nd wicket. This meant Tendulkar would be batting. As a result, interest turned away from the foreigners and turned back to the cricket. Tendulkar, more than usual, bore the weight of the nation on his shoulders. Showing few signs of nerves, he moved through to 12 when his progress was interrupted by the tea break. (Yes, cricket has breaks for lunch and tea). I went for drinks for the group, returning to find our group in a human tsunami of a photograph for a local paper. Not people to let the chance of getting in the local rag, 50 or so locals swarmed them, falling over them, groping them. For all of my attention seeking, I was pleased to be absent from this group shot. After this photographic orgy, play resumed and shortly after tea, Tendulkar scored the runs to become the highest run maker in test history. 15 minutes of fireworks followed, noisy although ineffective in the bright, mid afternoon sun. 15 minutes of the nation celebrating their favourite son’s triumph. Andy Warhol once said everyone would get 15 minutes of fame. I’m happy enough to have witnessed a small piece of history with a small cameo featuring on Indian T.V.

No comments:

Post a Comment