India is many things to different people. It is a country rapidly evolving, yet at the same time, deeply traditional – a country of extreme poverty and the extremely rich, of new money and money so old that it has grey hair. Bombings in Mumbai are perpetuated by unwelcome guests to the country, while elsewhere guests are welcomed at mosques, temples, shrines and at the place of Buddha’s enlightenment. Visitor’s reactions to India are split — partly repulsed by the poverty, partly fascinated by the buildings and the history. It is indeed a land of contrasts; the most beggars in the world and the most millionaires, perfume shops compete with the odours of open sewers. All things, beautiful and ugly, exist in the same place, seemingly independent but maybe also very dependent on this juxtaposition. India may always be like this.

The viewpoint of the admittedly widening Indian middle class would differ from this way of thinking. To them, India is rapidly developing, bridging the gap between developing to developed. The same people take pride in India’s nuclear and space programs. The same people criticize authors like the writer of the novel “White Tiger” and dismiss concerns raised over the Dehli Commonwealth games. They would argue such comments are only made by foreign panderers and internal agitators, who present a view of India that is quickly sinking from view but the West still believes. But for all the development, for the glitz and glamour of Bollywood, of the IPL, for all the money, for most Indians, the reality of their life is more similar to Slumdog Millionaire than it is to the latest Bollywood flick. They still deal daily with poor hygiene, the lack of infrastructure, the lack of opportunity to receive higher education. The caste system, officially renounced, is still active, especially in discussions of rites of passage like weddings. In Rajasthan, there have been recent accounts of enforced sati (the burning of the wife on her husband’s funeral pyre) reported. Honour killings are still commonplace here. Literacy, while improving (notably in socialist-controlled parts in the country) is still low, particularly for women. Rajasthan has one of the lowest literacy rates in the country.

We had travelled through Rajasthan for about three weeks, spending time in the pink city of Jaipur, ridden camels in the desert near Jaisalmer, admired the Lake Palace of Udaipur and wandered around the fort and maharajas palace in the blue city of Jodhpur. Last stop in the state was Bikaner, a dusty, desert, frontier town. The main attraction here was the Karni Mata Temple at Deshnoke, 30 kilometers out of town, about an hour on a tuk-tuk. This temple has become somewhat of a draw card on the Rajasthan loop. The draw card of Karni Mata is definitely not the temple itself, a rather scruffy, somewhat bedraggled looking building. Rats were the sole reason to be here. Commonly known to travelers as the rat temple, Karni Mata is a place where the lowly rat is King or Queen, where the rat is worshipped and fed. The rats are worshipped as the reincarnated son of Karni Mata, a Hindu sage who was herself the reincarnation of the goddess Durga. Outside, beggars go hungry around the outskirts of the temple while inside rats feast.

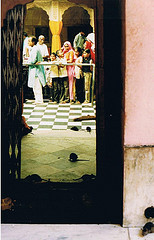

The rat temple has been featured on New Zealand TV, a weird homage to the rodents that are vermin everywhere else. Spending time in India does lend itself to multiple sightings of rats, as they are all over railway stations throughout the country. Here, rats are not persecuted, but feted, held in adulation. The most auspicious rat was a white rat. Seeing this guy was considered especially good karma. Another way to obtain good karma was to eat food tainted by rat saliva. I have to hope my karma stocks were high, as this way of obtaining karma was unlikely to happen. In the entranceway of the main temple were stacked stocks of fruit, rice and coconuts that pilgrims could buy and give as offerings to the rats. Musicians played, partly busking, partly in worship.

As we entered the building, rats became quickly apparent. Some were obviously sick, some were dead but most were active, drinking from the many trays of sugared water that lay around the temple grounds. The rats didn’t seem to mind the people, nor the people mind the rats. In fact, it almost seemed normal that these animals, usually considered reprehensible, were the focus of worship. As we walked around, we saw rats hanging from the walls, from doors, doorknobs and doorframes. Others were content to laze about in the open, with none of the constant scurrying associated with rodents. It paid to tread carefully. If you trod on a rat and killed it, you are supposed to replace it with a gold one (not gold coloured but a rat made from gold).

In one corner, there was a flurry of activity. A group of worshippers clustered, the white rat had been found. Once found, the poor creature was hounded. If a sighting was auspicious, imagine how much karma could be bought with a simple touch. Of all the rats, the white one was the only one that seemed agitated, fleeing under a table like a publicity shy celebrity hiding from the paparazzi. It eventually managed to find a hole in which to hide itself, much to the disappointment of the collected crowd. Deprived of the white rat, the locals turned to the next best thing; a group of tourists. We were inundated with requests for photos, mostly from young men, who were clearly not just taking photos of us and with us but taking the opportunity to record videos of us. I guess for them after the white rat left, the big prize remaining in the temple was the foreign women and to a lesser extent, the foreign men. While this transfer of interest was taking place, I imagined myself as the white rat, bewildered and confused by the attention. Am I really that much different that people would want my photo or clandestinely take a video of me?

The thing is that maybe we are that different. Foreign tourists like us must seem like the end point that lower to middle class Indians aspire to, representatives of a end-point that middle and upper class Indians think that India is obtaining. These same people would decry Western portrayals of India as cliché and bound in half-truths but who must know that there is still much to do before India can reach its full potential. Maybe in the way that the white rat was desirable, what we represent is desirable. Our presence serves as a reminder to what India could be, if it wasn’t so crippled by its contrasts. The white rat promises a better life through karma. Are we the white rats promise?

No comments:

Post a Comment